This week I was delighted to receive a letter seeking permission for the little book Watch with Me to be translated into Slovenian. Publication of the new edition next year will mean Watch with Me has been translated into six languages. More could be on the way. The continuing interest in the book is its fascinating insight into the evolving spiritual life of Cicely Saunders, and how that journey inter-twined with her work in hospice care. For this reason, I’m often asked how it came to be published.

How the book began

The idea for Watch with Me came after Dame Cicely gave me a copy of a lecture that she had delivered at Westminster Cathedral in June 2003 – and asked me if it could be published somewhere. I read it with interest but concluded that it would be better as part of a small collection of similar writings.

Further exploration of her relevant publications identified four other pieces that I thought worked together in a complementary way. Surprisingly it turned out that they were each written in a different decade, from the 1960s onwards. Cicely was immediately happy with the choice, so in a moment of hubris I set up a small imprint to publish the collection privately, took the cover photograph myself, and created a design for how the book should look and feel. It came out later in 2003 and over time two full print runs were sold, of about 3,000 copies in total.

At Cicely Saunders’ Memorial Service, which took place in Westminster Abbey in March 2006, Dr Robert Twycross gave the eulogy. Like others present that day, I was surprised to hear him say:

‘Many of us have read Cicely’s biography. I wonder how many have read Cicely’s autobiography? It is a slender volume entitled Watch with Me, and contains five reflective articles written and delivered over a span of 40 years. The last piece, Consider Him, is dated 2003. In little over 10 pages, Cicely recounts the salient points on her pilgrimage through life, and tells again the constant inspiration of her faith’.

It was a remarkable acknowledgement of the little book and seemed to inspire others to seek it out.

Translations and wider interest

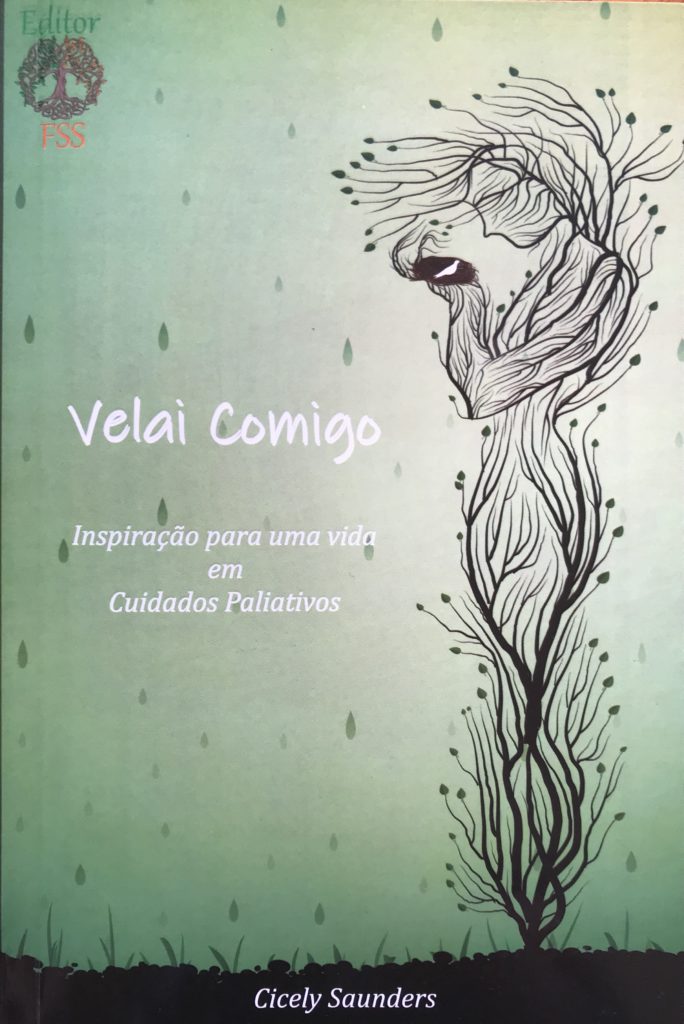

In 2008, the Milan based palliative care physician, Augusto Caraceni, together with colleagues, produced an Italian edition. The next year, 2009, a Swiss pastor and postgraduate student Martina Holder-Franz translated it into German. Spring of 2011 on a glorious day in Majorca, saw the launch of the Spanish edition, translated by Marisa Martin, Susan Hannam, Carlos Centeno and Enric Benito. Towards the end of 2013 the Portuguese edition was published, translated by Francisco Galrica Neto and with revisions and a preface by Isabel Galrica Neto. Then in 2018 Franklin Santana Santos produced a version in his native Brazilian Portuguese.

Watch with Me has been widely cited and well reviewed. Reena George, writing in the Indian Journal of Palliative Care described it as ‘a unique source of inspiration and information for anyone interested in palliative care’. There is every chance that other editions and translations will appear in the future and I am always happy to help with any practical arrangements to encourage this.

Key themes of the book

Running through each of the five chapters of Watch with Me is the relationship between personal biography, the emergence of the spiritual life, and a deep concern with the ethics of care.

The eponymous opening chapter is taken from a talk given at the AGM of St Christopher’s Hospice, in 1965 – two years before the hospice opened. It is about foundations – material, practical and above all the foundations of care, taken from words spoken by Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane. It sums up the demands that will lie ahead – and the importance of ‘being there’.

The second chapter, from 1974, is about faith and takes its inspiration from patients at the hospice. It also chimes with the mood of the day, quoting Tolkien’s metaphors of quest to demonstrate how, despite the worst adversities, ‘release comes unexpectedly and in the end all are seen to have played a part’. Faith, she says, can be about letting go as well as receiving with open hands.

‘Facing death’, the third chapter, was written for a Catholic journal in the 1980s. It is a reflective piece containing the distillation of decades of personal experience in caring for dying people: ‘To face death is to face life and to come to terms with one is to learn much about the other’.

‘A personal therapeutic journey (chapter four) is a well known piece that first appeared in the Christmas edition of the British Medical Journal in 1996 and has been much enjoyed. It takes us to the wards of St Thomas’ Hospital in World War Two, to reflections on the armamentarium of the day (including the Brompton Cocktail) and then on to the path breaking concept of ‘total pain’, which she first described whilst working at St Joseph’s Hospice in the early 1960s.

The collection concludes wonderfully with ‘Consider Him’, from 2003, where Cicely outlines for readers new and old the elements that make up her modern philosophy of care for those at the end of life – along with its sources, inspirations and dilemmas. She acknowledges that ‘Hospice and palliative care today is carried out by many people who find that religious answers do not speak to them. Nevertheless they give much spiritual help. When I asked our chaplain what was the real foundation for his work, he said simply brokenness’.

Cicely Saunders travelled a long way in her thinking and beliefs from the beginning of the book, where her main concern is to take a biblical text and apply it to the work of the hospice, to by the end a much broader set of reflections on illness, dying and death and their relationship to belief. The journey is fully revealed in five short chapters and stands as a remarkable testimony to faith and work in the life of one person. I encourage anyone to read it alongside my biography of Dame Cicely, which was published in 2018, to mark the centenary of her birth.

Continuing worth

Watch with Me is now out of print in English and can be hard to obtain. Second hand copies seem to trade significantly above their modest initial selling price. If you are fortunate enough to have a copy already, take it out over the Easter weekend and explore the rich messages that it still has to offer. As I have found oftentimes, it repays re-reading. If you don’t own the book – fear not. It is available here as a free download – Watch with Me full text 2005 (PDF) along with Watch with Me cover details 2005 (PDF)

I have a copy of Watch with Me signed by Dame Cicely and dedicated to my mother, who died in the spring of 2010. I will be reaching for it again this weekend.