I drive past a statue of Jean Armour, the wife of the Scottish poet Robert Burns, every morning on the way to work. When my 4 year old daughter, travelling with me, asked me about the statue, I told her it was to celebrate the life of someone who had died; that the woman must have done something special and because of that they made a statue of her. Each morning, as we drove past the statue, she would ask the same question, and each time I would try to find a different form of words to communicate ideas about memorialization in a way which was intelligible to her.

Not long after these questions about the statue started, other questions about death began, along the lines of ‘why do people die?’, ‘where are granny’s mummy and daddy?’, ‘Why did they die?’, and, more troubling, ‘I’m scared of dying mummy, I don’t want to die.’ As this was my first-born child who was asking, I had no experience of how to respond nor any clue about whether such questions were ‘normal’ at age 4.

My immediate thought was whether work discussions (I study and pontificate about death and dying for a living after all) had found their way to her impressionable young mind. But I welcomed the challenge her questions presented. Some cursory internet searches revealed that it is quite common for pre-schoolers to ask questions about death, and that honest responses using age-appropriate language is what is called for.

In my professional capacity as a university lecturer I often find myself advocating for more honesty and openness in discussing death and dying and I saw this as an opportunity to practice what I preach. I explained to my daughter that everybody dies and that this is part and parcel of being human. I told her that she wouldn’t die for a very long time, probably when she was very old and maybe even when she felt very tired and ready to die.

This brought home to me ideas which I had published earlier in the year about the idea of living a ‘completed’ life or being ‘tired’ of life when in the fourth age of life. Feeling ready to die when one is old could be framed positively, a noble end to the perennial struggle for survival and not necessarily to be viewed as a defeat or a manifestation of depression.

Interestingly, my daughter has no conception of age. She has never spoken of her grandparents as being ‘old’, nor has she spoken of death and dying in relation to them, noting only the absence of their ‘mummies and daddies’, her great grandparents.

Death education is what I do for a living. I teach an undergraduate course called Global Challenges at the End of Life, here at the University of Glasgow’s campus in Dumfries.

The course explores the global dimensions of death, dying, and care at the end of life, and we encourage students to critically assess the competing claims that are made about what constitutes a culturally appropriate or beneficial intervention at the end of someone’s life. The course is closely aligned to the Wellcome Trust funded project we run here.

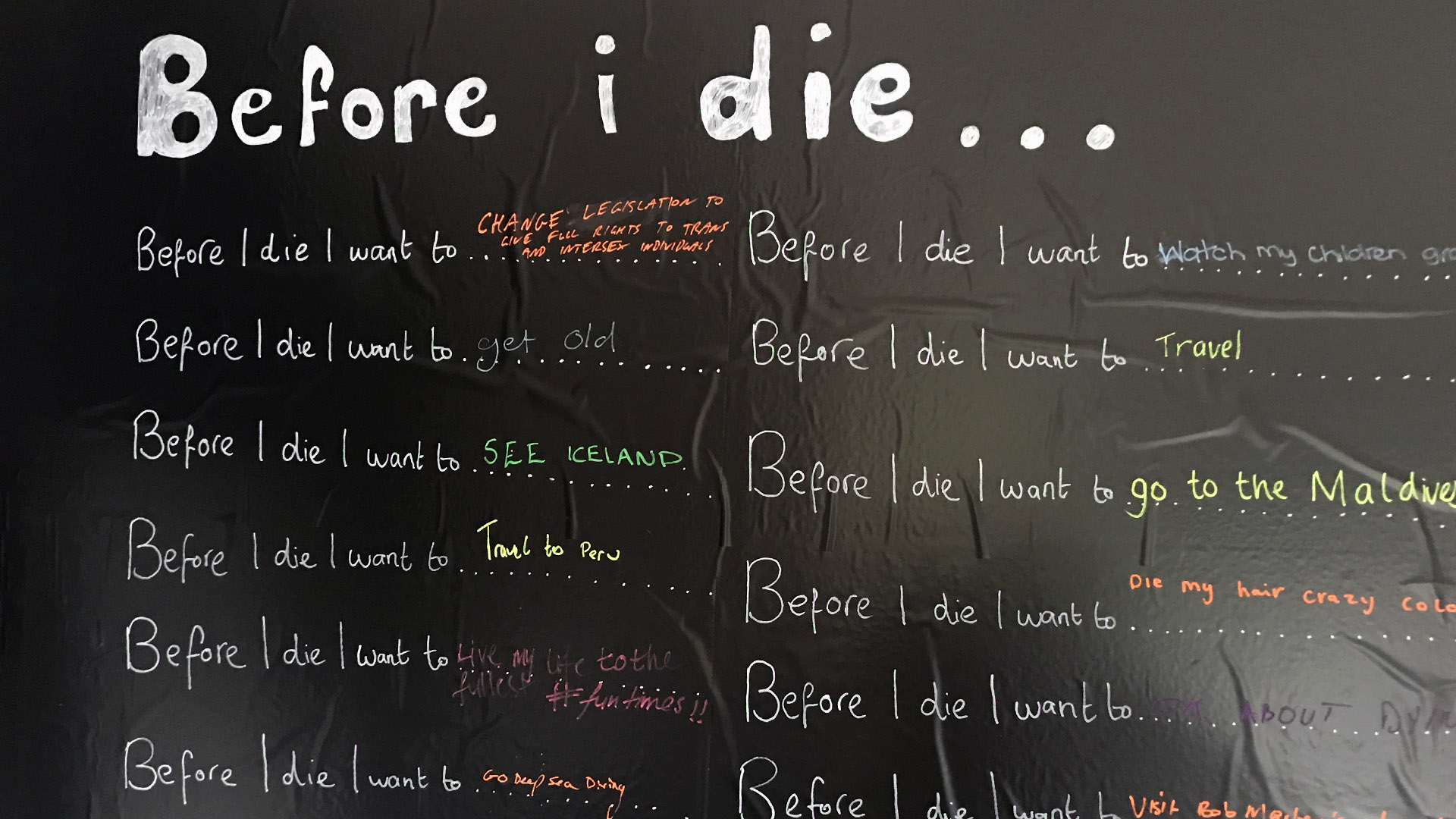

This year’s ‘class of 2017’ had their first seminar this month and we discussed ‘the good death’, ‘bucket lists’ and made a ‘before I die wall’.

Each year I teach this class I am surprised by how ‘experience near’ death is, even in a country where we apparently deny death at every turn. There is always a mixture of students who take this class – social science students, environmental science students, and those studying to be primary school teachers. I always try to encourage those training to be teachers to think about ways they could engage their own classes with the topic of death and dying, something which has been discussed in the academic literature.

While I have never spoken to children en masse about it, I have had conversations with my own kid and with other parents who have had similar conversations with their own kids. Children are naturally inquisitive about the world and their place in it and I have come to the view that it is best to respond honestly and openly to their existential questions. If we do this from a young age then we can perhaps ‘normalise’ talk about death and dying, which could benefit those children further down the line when they experience death more directly in their family or community.

My daughter has now started school and no longer travels with me to Dumfries, so she doesn’t see the statue of Jean Armour anymore. But she remembers it.

The other night she again told me she didn’t want to die and was scared of dying. Again, I reassured her and asked her why she was so scared. ‘Because I don’t want to turn into a statue.’ As it turns out, my comment that ‘they make statues of people when they die’ had been taken literally. After all, how was a 4-year-old to know that a life-size and lifelike statue was not a real dead person, frozen in suspended animation? I was relieved to get to the bottom of her fear of death, for now at least.

Let this example of the literalism of a young child’s mind act as a warning about using euphemisms for death. I can just imagine the confusion which would ensue from talking of someone ’croaking’ or that they ‘kicked the bucket’!

Naomi Richards

References

- Paul, S., Cree, V.E. and Murray, S.A. Integrating palliative care into the community: the role of hospices and schools. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care.

- Richards, N. 2017. Old Age Rational Suicide Sociological Compass 11:e12456. DOI 10.1111/soc4.12456

- Robinson, S. and L. Howatson-Jones 2014. Children’s views of older people. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. 28(3): 293-312.

- Smith, R. 2012. Richard Smith and Nataly Kelly: Global attempts to avoid talking directly about death and dying. theBMJopinion.

- VanClay, M. 2016. How to talk to your pre-schooler about death. BabyCentre.