Dr. Marian Krawczyk and Dr. Haruka Hikasa

Mitori Project

The Mitori Project was a multidisciplinary project examining end of life issues in the UK and Japan, led by Professor David Clark. It brought together academics from both countries using perspectives of social science, humanities, and ethics to examine how care of people at the end of life is currently organized within these countries, and shaped by relevant cultural, demographic, professional and policy factors. Dr Haruka Hikasa and I were responsible for the ‘practice stream’ of the project. We broadly interpreted this as focusing on actors, objects, and processes within end-of-life care practices. In that spirit, we conducted a comparative history of the development and implementation of advance care planning (or anticipatory care planning as it is called in Scotland) as it proved to be a compelling field of end of life practice around which to build comparisons between the two cultures.

Anticipatory/Advance Care Planning

A major task within organized health services regarding improvements in public health is to not only respond to health problems after they have occurred but to provide anticipatory care. One form of anticipatory care is through what is commonly known as advance care planning (ACP).

“Advance care planning is a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care. The goal of advance care planning is to help ensure that people receive medical care that is consistent with their values, goals and preferences during serious and chronic illness”.

(Sudore et al., 2017)

Healthcare in both Scotland and Japan is publically funded, although there are also a variety of private healthcare services. The government of both countries have exhibited increasing interest in developing health policy and care practices for implementing advance care planning on a national level, in part due to similar concerns for ageing populations, heavy demand on health and social care systems and changing social expectations about dying, death and bereavement. This is evidenced in two relatively recent advance care planning documents designed for public use.

- “Korekara no chiryo・kea ni kansuru hanashiai-Adobansu・kea・puranningu [Discussions about future treatment and care – Advance Care Planning]” (Yoshiyuki Kizawa ed., Commissioned by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, Revised March 2018)

- “My Anticipatory Care Plan” (Health Improvement Scotland, issued June 2017).

One of our approaches to understanding the practice of anticipatory/advance care planning was to conduct an analysis of the words used in each document. Closer examination of these two documents helps us understand the ideological similarities and differences regarding anticipatory care planning within Scotland and Japan’s governmental and health systems (including their priorities and goals) as well as the cultural frames within which these priorities and goals are expressed. In this blog we provide an overview of the results of our comparative content analysis.

Methods

We each generated an initial word list from our respective country’s documents, trying to honour the immediate context of the words (e.g. not separating ‘telephone’ and ‘number’ if they appeared immediately next to each other). Dr. Hikasa then translated her words/phrases into English. Words/phrases had to be used a minimum of twice to be counted, and we also counted how many time each was used. We then looked at how to best categorize these words/phrases within and between documents. After much discussion, and working with a professional interpreter for an afternoon, we created the following categories: 1) Medical-Health (words relating to health care and/or medical treatments); 2) Individual (words relating to personhood, values and wishes); 3) Relational (words describing relationships and connections of the person filling out the form); 4) Future-conditional (words relating to the future or future possibilities); 5) Administrative-legal (words relating to administrative and/or legal tasks); and 6) Other (uncategorized words). It then took two rounds of further discussion to reach a general agreement about which words/phrases belonged in each category.

What We Found

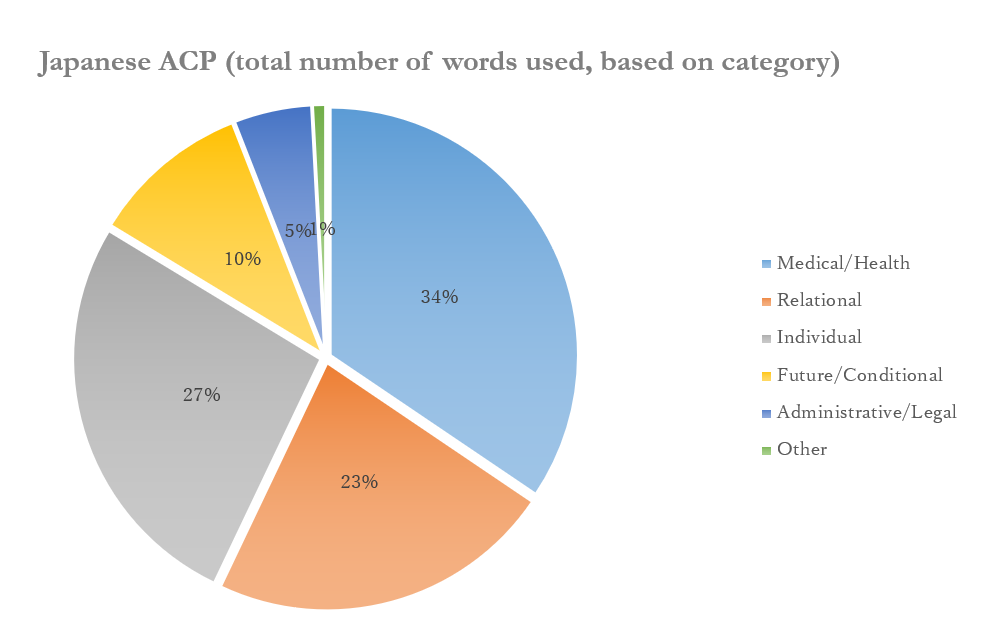

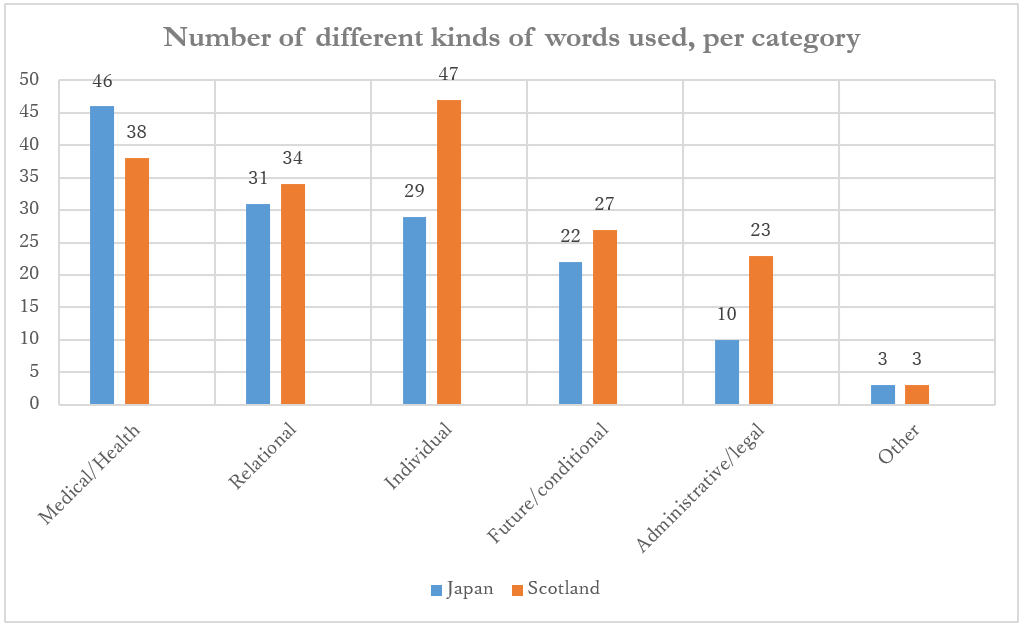

First there were significant differences in length between the two documents. The Scottish ACP form is 36 pages long, with 1515 words or phrases that are used at least twice. The Japanese ACP form is much shorter; 14 pages long, with 827 words/phrases that are used at least twice. Below, the first two charts show the number of words, in percentage form, used within each category. The third chart enumerates and compares the number of different types of words used within each category between the two documents.

Highlights

- Medical/Health: Even with the significant differences in length of the two documents, the Japanese document had a much higher ratio of medical and health word used (34% versus 16%) as well as kinds of words, than the Scottish ACP (48 different words versus 36).

- Relational: There was a similar number of the kinds of relational words used between documents. However, there was a significantly higher overall number of words used within the Scottish documents versus the Japanese one (30% versus 23%).

- Individual: There were significantly more kinds of words used in the Scottish document signifying individuality versus the Japanese document (47 different words versus 29). However, this higher number of different words used did not transfer to any larger percentage – both documents have very similar proportion of words used to signify individuality.

- Future/conditional: There was a significant difference in this category, with the Scottish document almost twice as often using future or conditional words as the Japanese document (17% versus 10%). However there was relative similarity in the kinds of words used.

- Administrative/legal: Considerably more kinds of English words were used to signify administrative and legal concerns than in the Japanese document (23 different words versus 10); as well as a significant amount of English words were unique (had no comparable words within the Japanese document).

- The Scottish ACP used the term “end of life” and “death” whereas the Japan used more conditional language such as “life-threatening”, “severe”, and “life-prolonging”, “at that time” and “in emergency”.

- On the other hand, the Japanese document used much more explicit medical terms overall, such as “ventilator”, “ICU”, and “tracheal intubation”. However, the Scottish ACP used some variant of the term “cardio pulmonary resuscitation” 17 times, while the Japanese document only used this term twice.

- The Japanese ACP did not use terms found in the Scottish ACP such as: “home”, “organ donation”, “consent”, “control”, “choice”, or “responsibilities”.

- The Scottish ACP did not use terms found in the Japanese ACP such as: “suffering”, “burden”, or “hope”.

- The Japanese ACP did not use the terms “advance directive”, “advance statement”, or “power of attorney” all which were part of the Scottish ACP.

- The Scottish ACP has a “Summary of Clinical Management Plan” to be filled out by a “lead healthcare professional”, and shared/held by the person’s GP. The Japanese ACP has no equivalent, nor are there spaces for phone numbers, addresses, or signatures, which are part of the Scottish ACP.

Discussion

Our analysis finds relative similarities in the number and kinds of words across the two ACP documents, as well as some interesting differences. Of particular note is the relative weight given to “health and medical” terminology in the Japanese ACP in comparison to words about relationships or individuality. If implementing advance care planning is aimed at sharing personal values, we can see that the Japanese ACP form is intended to discuss more specific medical care issues, whereas the Scottish ACP only references CPR. We find this particularly interesting because it indicates a straightforward approach in Japan to discussing medical events common in end-of-life care, yet the Scottish document makes more explicit references to the end of life and death.

We also find the higher percentage of “relational” word usage in the Scottish ACP in comparison to the Japanese document an interesting one, even as they share similarities in the kinds of words used to indicate relationships. On the other hand, while the Scottish ACP uses many more kinds of words to indicate individuality, both documents are exceptionally similar in the overall emphasis on personhood.

Although both documents are designed to stimulate thinking about future conditions or possibilities, the Scottish ACP uses significantly more words generally emphasizing this concern in comparison to the Japanese ACP. Finally, the Scottish ACP gives almost twice the weight to administrative and legal concerns than the Japanese ACP. This indicates major differences in the documents’ purposes; in Scotland an important focus is ensuring its citizens organize bureaucratic paperwork and generate medial information for (and increase GP use of) the Key Information Summary (an electronic patient record). There is no such connection to patient medical records in Japan.

A Note of Caution

Much of our face-to-face work on this project was conducted with assistance of translators. Dr. Krawczyk has no previous experience with the Japanese language, and Dr. Hikasa is not fully bilingual. The challenges of such a complex analysis across very different languages proved to be too complex to formally publish the results of our work. However, we have spent a great deal of time in carefully discussing, cataloguing, and developing this analysis. We believe that as a ‘first attempt’ to do this kind comparative work has resulted in new and potentially significant insights that can benefit policy-makers, health care providers, and others interested in anticipatory/advance care planning.

Future Directions

Overall our research on the historical development of anticipatory/advance care planning in the two countries finds common themes in the concern to reduce medical costs and hospital admissions, as well as the tension between autonomy and control versus relational perspectives. But these over-arching themes give way at the national level to differences in the amount of information resources that are available, the varied links between ACP and medical records, and the direct and indirect connections to larger health policy goals. Our close analysis of Japan and Scotland’s respective ACP documents provides a new perspective about the ways in which end-of-life care planning between the two countries are ‘practiced’. We are currently finishing a publication about the historical policy and practice development of ACP planning in each country. Please do be in touch if you’d like to discuss this work further.

Sudore, R. L., Lum, H. D., You, J. J., Hanson, L. C., Meier, D. E., Pantilat, S. Z., … Heyland, D. K. (2017). Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition from a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 53(5), 821–832.e1

Dr Marian Krawczyk

Lord Kelvin Adam Smith Fellow, University of Glasgow

Marian Krawczyk is a Lord Kelvin Adam Smith Fellow and member of the Glasgow End of Life Studies Group. She obtained her PhD in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Simon Fraser University (Canada, 2015). Her research was an ethnographic study of hospital palliative care specialists and patients, and how they collectively negotiated the dying process within increasingly complex health systems. Before joining the University of Glasgow she held several post-doctoral positions in partnership with Trinity Western University (Langley, B.C.), The Centre for Health Evaluation and Outcome Sciences (Providence Health, Vancouver, B.C.), and The Canadian Frailty Network.

Dr Haruka Hikasa

Senior Assistant Professor, Okayama University

Haruka Hikasa has been teaching at the Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering in Health Systems at Okayama University since April 2018. Her research interests broadly include surrogate decision making, end-of-life decision making, autonomy, best interests, and possible practical instruments for decision-making processes. She is currently working on the significance of patients’ preferences and affections and the role family members or healthcare providers play in end-of-life decision making. She majored in Bioethics and obtained her PhD from Tohoku University in 2013. Her research was on the consideration of respect for autonomy and patient’s best interests in decision making in healthcare regarding life and death.

Very interesting report. The comparisons between the two countries in their approach to their research are remarkable and thought provoking. In the coming together one gets the sense that the differences in language and approach are both made difficult by these differences, but also made richer in many ways. Will be interested in hearing further developments in these studies.