Cicely Saunders died on 14th July 2005. I was running an international end of life care summer school at Lancaster University at the time. That evening, staff and students gathered in the home of a colleague: the summer school party had turned into a wake. I read out a draft of an obituary I had been asked to prepare some weeks earlier and afterwards, we pondered tearfully on a life well lived and the remarkable legacy of a great hospice and palliative care leader. It is a legacy that continues to unfold.

In the last months of her life Cicely was cared for at St Christopher’s, the hospice she had founded in 1967. At first, as on previous occasions when she had been admitted, she enjoyed casting a close eye on how the place was running and the quality of care being delivered. But as her condition deteriorated significantly, she began to receive a daily flow of visitors, wishing to say their goodbyes. I was one of them.

In 2005, I saw her twice at the hospice. In June, I was there to say my own farewells. But a few months earlier in March, I recorded the last of over 20 interviews I had been conducting in the previous years, with a plan I had agreed with her – to write a biography after she had died.

You can listen to a small section of that last interview here, and enjoy hearing Cicely in excellent spirits, despite the problems she was facing. It may well be the last recording made of her speaking:

Memorial Service and Watch with Me

Since her death, and after the initial period of grief and loss, many people have organised ways to remember Cicely.

Her memorial service in Westminster Abbey on 7 March 2006 saw a packed congregation from many countries and corners in a calm, but reflective mood. One extended tribute by Dr Robert Twycross was eloquent in teasing out Cicely’s personal and professional qualities and portrayed her as the ‘wounded physician’ who, through her own sorrows, had learned to empathise with and support the patients and families who came under her care. He described the short selection of pieces by Cicely that I had edited in the volume Watch with Me, as her ‘autobiography’: five essays written over five decades, mapping out her approach to hospice, and contained within an exploration of her unfolding religious belief and practice.

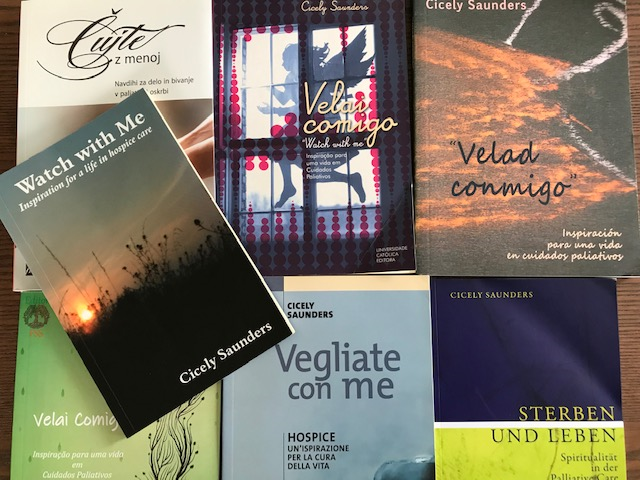

First published in English in 2003, with Cicely’s close involvement, editions of Watch with Me have appeared subsequently in Italian (2008), German (2009), Spanish (2011), Portuguese (2013), Brazilian Portuguese (2018), and Slovenian (2019). Other translations are in the pipeline. The interest in that book is extraordinary and is seen by some palliative care commentators, such as Philip Larkin in his work on compassion, as key to keeping alive a particular vision of care at the end of life (1).

A decade on from her death

We saw further evidence of this when, 10 years after her death, in an event called Remembering Cicely, a number of her family, friends and colleagues gathered at St Christopher’s for an afternoon of recollection. Among the touching personal memories, there were also contributions which pointed to the unfolding legacy of Cicely’s work. For example, Professor Irene Higginson, Director of the Cicely Saunders Institute, highlighted the international spread of hospice and palliative care and in particular the milestone resolution, passed one year earlier by the World Health Assembly, calling on all governments to integrate plans for palliative care into their national health strategies.

But despite these achievements, within a decade of her death, some concerns were also being raised about Cicely’s diminishing influence and the threat this posed to the ‘essence’ of palliative care . There was a sense that some aspects of her early vision and direction were being lost, thereby stimulating countervailing arguments about maintaining and nourishing her underpinning ideas and Christian beliefs and their relevance to contemporary palliative care.

Towards the end of 2015 another significant milestone was achieved in securing Cicely’s legacy. After much work over a number of years, described by me here in a short talk, the Cicely Saunders’ archive was fully collated and opened for wider access at King’s College London. It is a remarkable treasure trove of material that will fascinate anyone interested in her life and work.

Relevance today and recent work

Fifteen years on from her death, there should be no doubt that Cicely Saunders is still being remembered. This may be as a revered iconic figure in the field, as a complex founder of a multi-facetted movement, and perhaps in particular as both a source of further learning and an object of study in her own right. I tried to tap into all these dimensions as I wrote her biography for publication on the 100th anniversary of her birth on 22 June 2018. For me this was a huge personal landmark, that completed a trilogy in which I had previously edited both her letters and her selected writings in two volumes, which now sat alongside my account of her life in a work of 150,000 words.

Very quickly the Saunders archive has become a stimulus to further scholarship. Notable to date is the work of Joe Wood, a postgraduate research student in English literature at the University of Glasgow, who is in the final stages of a doctoral thesis, digging deep into her writings, and entitled “Cicely Saunders and the Legacies of ‘Total Pain’”.

This forms part of a wider body of academic work on Cicely’s famous characterisation of ‘total pain’ that goes back to 1999, and which is reported elsewhere on this blog in our most-read post ever, and to which we returned in a special issue of the journal Omsorg.

In 2018 my colleagues Dr Marian Krawczyk and Dr Naomi Richards also published a paper on ‘total pain’ in palliative care practice and policy, a theme taken up in a doctoral dissertation being prepared by Claire Morris. More recently Dr Krawczyk has taken this in new directions with her work on total pain and the brain-gut axis.

Elsewhere, there are other examples of the continuing interest in Cicely’s work. I recently came across a long article entitled ‘The Modern Hospice: Cicely Saunders’ theological-philosophical foundations’ by Dr Komuves Sandor. It’s in the journal Kharon, has an abstract in English, and looks highly recommended for those able to read Hungarian.

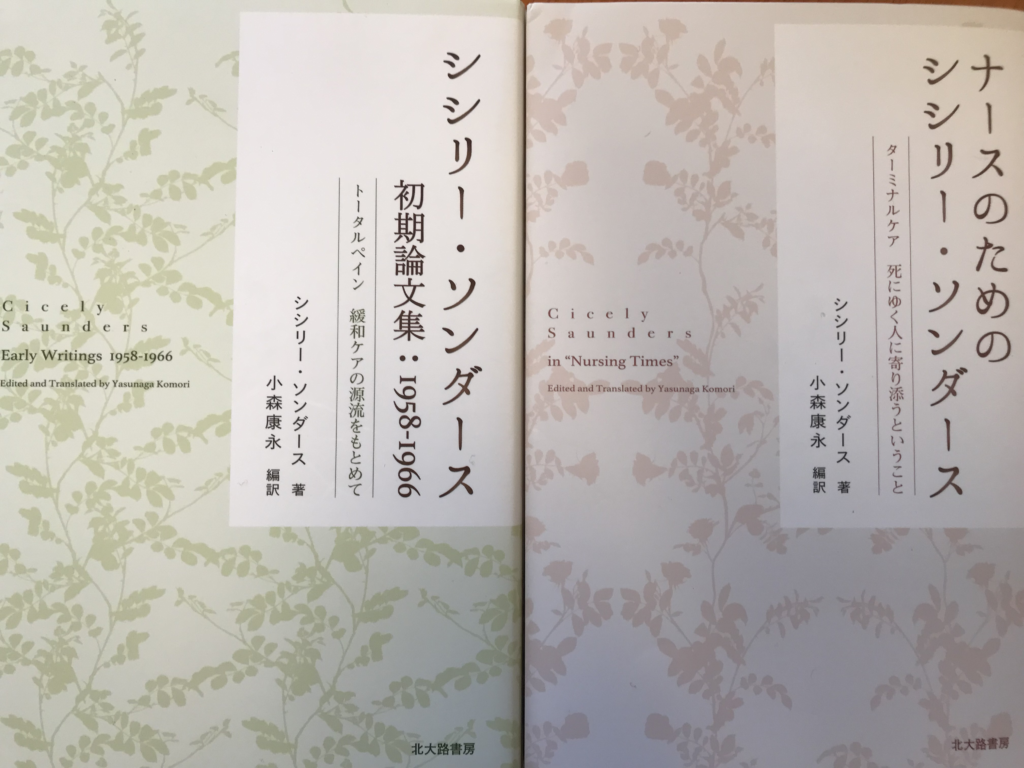

In Japan, the psychiatrist Dr Yasunaga Komori has recently edited and translated two volumes, one of “Cicely Saunders Early Writings 1958-1966” and the other a collection of Cicely’s writings in “Nursing Times”.

In Italy, a working group of doctors has formed to give deeper consideration to Cicely’s writings and ideas. In 2018 they published a paper entitled The Path of Cicely Saunders: The “Peculiar Beauty” of Palliative Care The authors take the view that Cicely’s work is ‘always to be rediscovered’ and is still today the most convincing conception of palliative care.

The Cicely Saunders Society

Evidence of this kind of interest from around the world led a group of us in the UK in June 2019 to form The Cicely Saunders Society to promote appreciation and understanding of the life and work of Dame Cicely Saunders. Its objectives are:

- To organise intellectual and sociable activities and events for members, including visits to sites and places of interest, symposia, seminars and lectures.

- To promote activities to further identify and safeguard archival material relating to the life and work of Cicely Saunders, including the digitisation of relevant papers, and the cataloguing of publications and writings, as well as photographic, film and sound recordings

- To consider how learning from the life and work of Cicely Saunders could apply to contemporary issues and thinking related to hospice and palliative care

- To carry out any other relevant activities in pursuit of the aim of the society.

I spoke about its aspirations and ideas for development at the 2018 Hospice UK conference, though plans for other events this Spring and Summer have been overturned by the COVID-19 epidemic. A lively Twitter presence does gives the Society visibility however and is a source of fascinating updates and vignettes from the past. You can follow it here – @CicelySociety. I am hoping that the Society will re-kindle its plans as soon as circumstances are right.

So much more to be learned …

At the very end of her biography, paraphrasing something once said to her, I wrote that ‘there is so much more to be learned about Cicely’. I recently had a striking example of this.

A few weeks ago Sharada Bhat tweeted the following from Cicely: ‘Clenched hands are lonely, unrelenting, closed in. Open hands are vulnerable, accepting and a symbol of the faith that can receive and be blessed, over and above all our imagining. They are ready for freedom and for spontaneity’. I confess to being puzzled about the source. Sharada clarified it for me: ‘Watch with Me’, page 13 the article entitled ‘Faith’. I had edited the book, read and re-read it many times, but still needed another person to introduce me to one of its rich insights.

Such is the legacy of Cicely Saunders. Long may it continue.

(1) Larkin P. Compassion. The essence of palliative and end-of-life care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016.

Very interesting account of a remarkable woman who had a vision of what palliative care could be and used her talent for communication to the fullest. Thank you David.

Thank you Betty for your continuing interest in our blog. Kind wishes, David