Professor David Clark, Dr Marian Krawzyck, Dr Naomi Richards, Dr Sandy Whitelaw, Anthony Bell – all members of the Glasgow End of Life Studies Group – share some recent insights.

‘Palliative care will assume a central and vital role in the care for patients in an influenza pandemic’

The importance of delivering effective palliative care as the COVID-19 epidemic unfolds is becoming more and more recognised. Whilst it is common to restrict the view of palliative care to the needs of patients who will not recover from the virus, palliative care also seeks to support the physical, social, psychological and spiritual needs of patients and their close ones, across the whole trajectory of illness. So the demands are huge and we see examples from correspondence with colleagues around the world of hospital-based palliative care teams being given massive responsibilities in specially designated coronavirus areas of the acute hospital.

We are sharing here some observations based on a rapid, non-systematic review of key literature on palliative care in pandemic and related contexts, such as humanitarian disasters of various kinds. We try to highlight some of the issues that require consideration. In doing so we want to contribute to the rapidly developing dialogue about COVID-19 and palliative care, which is occurring between service providers, researchers, community groups and others wishing to pool knowledge and information in the interests of informed strategies and collective action.

Learning from Critical Care

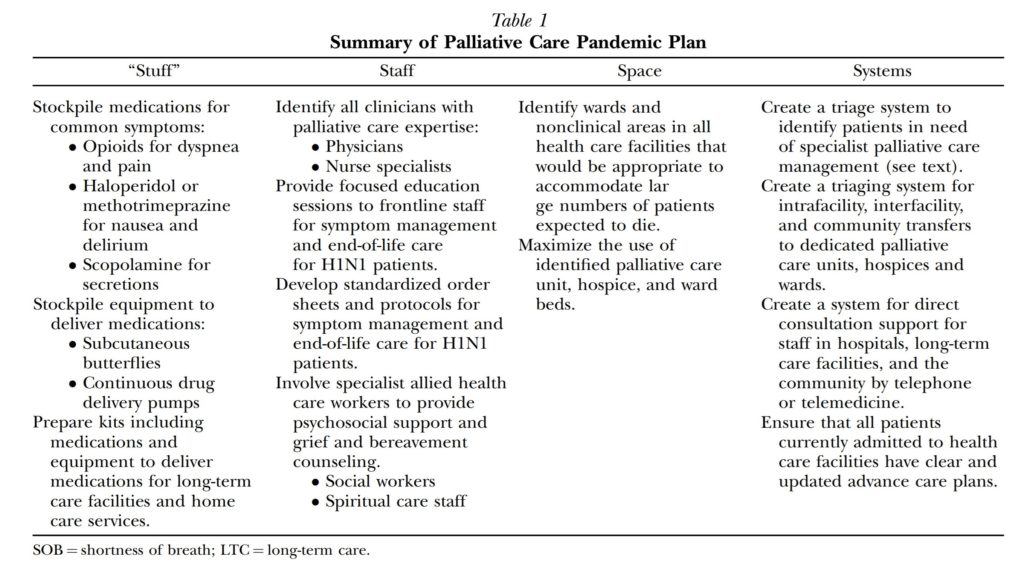

Critical care is the key model for providing ‘surge’ capacity during a health crisis and is captured in four key elements: ‘stuff,’ staff, space and systems. Downar and colleagues [2] in ‘Palliating a pandemic’ summarise these four components in relation to palliative care and provide a very practical table indicating some of the elements of each. Our thanks to colleagues at the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management for permission to reproduce this here:

Downar, James et al. (2010) Palliating a pandemic: ‘All patients must be cared for’, Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 39 (2), 291 – 295

This excellent article is therefore a go-to source at the moment for anyone wanting to look in ‘in the round’ at where palliative care should sit in the COVID-19 context. ‘Stuff’, ‘Staff’, ‘Space’ and ‘Systems’ is a simple mantra that can apply in any context – large or small scale – and seems to have immediate resonance with clinicians, managers and planners alike.

Triage

Triage is a fundamental aspect of the required approach to palliative care in a pandemic. Daubman et al (2019 [4]) take lessons from the provision of palliative care in humanitarian crises, and their points have a strong affinity with the current pandemic context. Triage is important in ensuring that all responders are mindful of the need for palliative care, even where acute interventions are concerned and where the expectation of recovery may be present. In a context of scarce healthcare resources and a with a triage system in place, some critically ill patients will almost certainly be denied life-sustaining treatment. However, a key principle of triage is that such patients will continue to receive care, including palliative care. Hospitals are therefore forming triage committees to undertake this work and to undertake arbitration where there are disagreements.

Special facilities

Cinti et al (2008) [5] describe a model for Alternative Care Centres (ACCs) providing off-site care when mainstream hospitals are overwhelmed in an influenza epidemic. Their modelling exercise used a series of basketball courts at a university campus for this purpose. A portion of the ACC was dedicated to the palliative care of terminally ill patients, confined to one of four ‘pods’. They discuss the following elements arising from their exercise:

- Location – non-clinical space could be adapted for use as an ACC (but see below the concern about palliative care) and assuming the availability of sufficient beds and other supplies.

- Admitting/patient flow – where patients self-referred there were bottlenecks and the facility became like an emergency room; where patients were referred from existing services then triage at the ACC was needed less and patient flow was smoother.

- Communication – these were mainly hardware issues (walkie talkies for internal use) and issues of communication with the main healthcare services externally (where sending and receiving timely information was challenging).

- Staffing – 40-50% of the workforce may be absent at the peak of the epidemic. Leadership positions in the ACC included: a group supervisor, a nursing unit leader, a medical operations unit leader, a medical care task force leader, a supply/logistics unit leader, a finance unit leader, and a records/planning unit leader. Job action sheets for these positions have been published. It was estimated that 22-28 staff (across grades and roles) could manage a 50 bed ‘pod’ within the ACC.

- Supplies and equipment – oxygen was needed for all patients; a medication formulary was developed – http://www.liebertpub.com

- Security – preventing unfettered access to the ACC was crucial.

- Palliative care – the modelling exercises found that a separate ‘pod’ for palliative care within the ACC did not work well: 1) it was sometimes under-used when other pods were full 2) transferring patients there from other pods exacerbated suffering 3) dying patients might be easier to manage in the main facilities rather than a ‘field hospital’ setting.

Impact of pre-existing and newly acquired morbidities

Nouvet et al (2018) [6] in a systematic review of the provision of palliative care in humanitarian crises, note the impact of pre-existing and newly acquired morbidities on palliative care needs. The categories of these patients identified in the literature as being at risk of dying or likely to die include:

(1) persons who were previously healthy but who became critically ill or injured by a disaster or high-fatality infectious disease;

(2) individuals who prior to the crisis were highly dependent for their survival on intensive medical care or with pre-existing life-threatening illnesses (e.g., on ventilator, dependent on dialysis, with advanced cancer);

(3) individuals in palliative and hospice care when a disaster strikes;

(4) those with chronic illnesses or comorbidities whose health deteriorates as a result of a crisis;

(5) individuals who require symptom control and supportive care while they await curative medical attention;

(6) any individuals likely to die when triaged out of curative medical care due to scarce resources.

Psycho-social issues

A study from a palliative care team in Singapore (Leong et al 2014) [7] highlights the psycho-social aspects of delivering palliative care from experience in the SARS epidemic. They list several problems associated with patient isolation, including a loss of self-esteem and autonomy, feelings of powerlessness, disruption of family relations and a sense of stigma. The uncertain progression of the disease led to inaccurate prognostication and uncertainty and difficulties in preparing for death. Many health care workers contracted the disease, and had their own fears and anxieties. System pressures meant that ritual observances associated with a death got curtailed or abandoned, adding to the suffering of family members and close ones.

Leong et al also note:

‘… palliative care teams have much to contribute in addressing the psychosocial and spiritual problems during an acute viral epidemic, such as suggesting measures to improve connectedness, training health care workers in bereavement counselling, training health care workers to communicate while in personal protective equipment, and implementing measures to help health care workers deal with stress’.

Conclusions

From our quick review, several messages stand out:

- Palliative care should be a central part of the overall strategy for managing the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Attempts to model the palliative care response to an influenza pandemic highlight the need for: ‘stuff,’ ‘staff’ ‘space’ and ‘systems’ and the elements of these have been detailed.

- A useful initiative has described the value of an Alternative Care Centre to meet excessive demand.

- Special attention needs to be given to transparent triage systems, consistently applied and to the provision of palliative care within these.

- Front line workers will need support in delivering appropriate psycho-social and spiritual care and in dealing with their own pressures and concerns.

Palliative care workers are now facing perhaps the greatest challenge in the history of their field. Rapid sharing of information and insights is made possible through the use of social media and mechanisms such as #pallicovid on Twitter and Gdoc sources like this one – https://tinyurl.com/t6lvzg5 We invite colleagues to use this Blog for further sharing and commentary and will continue to post material from our own group where it may be helpful to others.

[1] Rosoff, PM (2006) A central role for palliative care in an influenza pandemic Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9 (5), 051-3. DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1051

[2] Downar, James et al. (2010) Palliating a pandemic: ‘All patients must be cared for’, Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 39 (2), 291 – 295. https://www.jpsmjournal.com/article/S0885-3924(09)01143-9/fulltext

[3] Matzo, M Wilkinson, A Lynn, J Gatto, M Phillips, S (2009) Palliative care considerations in mass casualty events with scarce resource. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science, 7 (2) , 199-210. http://doi.org/10.1089/bsp.2009.0017

[4] Daubman, B.R., Cranmer, H., Black, L. et al. (2019) How to talk with dying patients and their families after disasters and humanitarian crises: a review of available tools and guides for disaster responders. International Journal Humanitarian Action, 4, 10, https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-019-0059-6

[5] Cinti, S K et al (2008) Pandemic Influenza and Acute Care Centers: Taking Care of Sick Patients in a Nonhospital Setting. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science, 335-348. http://doi.org/10.1089/bsp.2008.0030

[6] Nouvet, E., Sivaram, M., Bezanson, K. et al. (2018) Palliative care in humanitarian crises: a review of the literature. Int J Humanitarian Action 3, 5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-018-0033-8

[7] Leong IY et al (2004) The challenge of providing holistic care in a viral epidemic: opportunities for palliative care, Palliative Medicine, 18, 12–18. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm859oa.

This is a very important observation and can go a long way in helping manage patients infected with COVID-19. Especially envisaging that the current rate of infection large numbers of people may be involved making it challenging to manage them in hospitals and even care home. The focus may end up being home based or community based.

I think this is an excellent review of the needs of hospice and end of life care, which also serves as a blue print for the way forward in terms of coping with the current pandemic as well as future ones.

Thanks so much Betty, it’s great to have your encouragement from such a distance away. Kind wishes from all the team!

In this situation of confusion, isolation and abandonment, I found hope and courage .

Very timely piece with helpful guidance and directions. Thanks to Prof. David Clark and etal.

Thank you so much for this informative and insightful piece. As a community CNS in palliative care I have been very worried about our patients, as well as the pressure on our service as new referrals flood in due to cancelled treatments and clinics. We are all racing to adapt to the constantly changing global situation but it is really empowering at such a difficult time to know we can make a difference! Thank you!

It’s kind of you to comment Catriona. I hope we will be posting more material of this nature, and if you are on Twitter I am sharing relevant things I find, just like many other people – @Dumfriesshire All success in your work and keep safe. David Clark

[…] Palliative care will assume a central and vital role in the care for patients in an influenza pandem… […]

Dear David and co-works – Thank you for bringing forward and sharing this very important piece of knowledge in this special situation with a high numbers of people dying in Europe and globally. Your work has contributed to kick-start national knowledge gathering and sharing in Denmark trough REHPAs website. Wish you all a peaceful Easter.

Dear Anne-Dorthe, it is good of you to write this. Thank you. The piece is already one of our most read blog posts and seems to have found a very large audience in the palliative care world , just at a key moment. Curiously, the main paper on which we focus was published 10 years ago but seems to have had very little attention until now. All good wishes.

Palliative caregivers are absolutely essential in this crisis. Someone has to inform elderly or seriously ill people or their surrogate decision makers, help them to understand their situation, and then document their decisions. Having the opportunity to make decisions ahead of becoming ill with COVID-19 is especially important for those who decide to opt out of the conventional pattern of going to the hospital and being put on a ventilator. These are some difficult decisions to make but critical.

Many thanks for your comment Angelina.

[…] Ved End-of-Life-Studies hos vores kollegaer i Skotland, har REHPAs adjungerede professor, David Clark, og hans team gennemført et hurtigt (og ikke-systematisk) litteratur studie af viden om pandemier og palliation. De har fundet syv studier, der kan inspirere i forhold til en palliativ indsats under henholdsvis pandemier og humanitære katastrofer. […]