Coronavirus is changing the way we live in a way that is repeatedly said to be unprecedented. We say we are living through strange times, extraordinary times, difficult times. For some of us lucky enough to be able to work from home time might be stretching out in lockdown into an endless series of Thursday afternoons. For others, the increased workload at the moment might feel like time is rushing ahead of us. For those who have lost jobs or loved ones, time might seem to have stopped altogether.

My own PhD project seems at first to be unrelated to the current strange times. I am looking at the ideas of Cicely Saunders, who is said to have founded the modern hospice movement. Using approaches from the humanities and social sciences, I am examining what she wrote and the books she read to understand more clearly some of her thoughts about how to care for people when they are dying. Specifically, I am looking at Saunders’ idea of ‘total pain’ which understands that an individual’s pain at the end of life is a whole overwhelming experience – not only physical but also emotional, social and spiritual. Saunders worked with patients whose deaths were expected, from non-contagious diseases like cancer. However, my own journey to studying how Saunders thought about these kinds of deaths is in some ways closely linked to our current coronavirus experience.

The dissertation I wrote for my original degree in English Literature was on Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year. Written in 1722, as rumours of plague in Marseilles reached Britain, the book is a first person account of the Great Plague of London in 1665. It follows ‘H.F.’, a merchant probably modelled on Defoe’s own uncle, as he lives through a summer of contagion in the capital. Although in part made up by Defoe, the book includes much factual information about events at the time and is still used as a historical source of information about what the plague was like for those who lived through it.

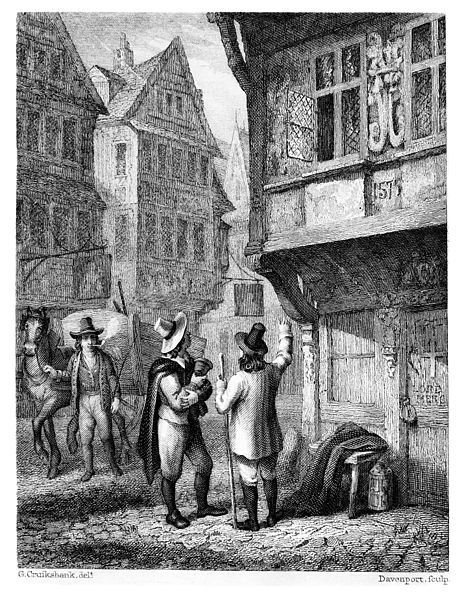

London Street during the Great Plague

Free to use with attribution Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

At the moment, I find my mind keeps going back to H.F.’s observations, many of which have direct parallels in our current crisis. He describes weekly ‘bills of mortality’ like today’s daily coronavirus statistics and sees people walking in the middle of street to avoid each other. He notes how panic spread faster than the disease itself with people believing hearsay or exploiting the desperation of others by selling quack remedies and ‘plague-waters’. He speaks to people who blame the plague on a passing comet, like those who burn down 5G masts today. He even notes how the lack of traffic in the streets means nature starts to reclaim public spaces.

Like current talk of ‘strange times’, Defoe’s narrator calls the plague ‘this Suprizing time’ (p.18) and as an undergraduate I was particularly interested in how Defoe communicated to his readers the strange temporal experience brought about by infectious disease. In some ways, the plague forces people to live only for the next moment, remaining vigilant for infection. At the same time, the possibility of soon getting infected and dying encourages people to comprehend the entirety of their lives up until that point so that every moment is charged with memories of the past and hopes for the future. Yet, simultaneously, such thinking is frustrated since their lives as they knew them exist in a temporal vacuum in which normal human interaction is impossible – a lot like our lives in lockdown at the moment. In my dissertation, I wrote about how Defoe used literary devices to show how the plague gave people this confusingly heightened sense of their own position in time

Later, I took a masters course in Medical Humanities where I thought I would continue to study the language and narratives we use to discuss infectious and contagious diseases. I imagined writing about the dog-whistle of colonialism in the way some Western journalists wrote about Ebola, or about how the language of contagion is used in public health contexts for epidemics of non-contagious issues like cancer or obesity.

Instead, I found myself drawn to how the sense of temporal confusion that Defoe so brilliantly communicated in his Journal has parallels in discussions of ageing, death and dying. Proximity to death can exert what Lynne Segal calls a sort of ‘temporal vertigo’ (Segal, 2013, p. 4) in which the relative shortness of future life compared to accumulated memories from the past means we live more in memories than in the present since a greater proportion of our experiences lie in the past than the future. This can be consoling, such as the process of ‘life review’ observed by psychologist Robert Butler in which older people are sometimes comforted by the process of going over past achievements (Butler, 1963). Yet, it can also be alarming if aspects of your life have been traumatic or disappointing. And it can be made even worse by the very present situation of an imminent death and the potential problems and medical interventions that accompany it.

I came across Cicely Saunders after attending a talk on death and dying and realised Saunders was thinking in the same way about time at the end of life. I started reading her written work and became hooked. As Saunders writes, a terminal diagnosis presents a person with ‘a crisis situation, with the joys and regrets of the past, the demands of the present and the fears of the future all brought into stark focus’ (Saunders, 1984, p. 51). This sense of time being experienced all-at-once is summed up, for me, in her idea of ‘total pain’, in which an individual’s pain is a whole overwhelming experience that can be affected by physical tiredness or fear of pain, but also boredom, regrets, and meaninglessness. By attending to the whole person ‘total pain’ recognises, as sociologist Yasmin Gunaratnam has suggested, how pain can be ‘accrued over a lifetime’ (2012, p. 109).

As well as this confusing experience of time, what I loved about Defoe’s Journal and what still moves me about Saunders’ writing is how they both describe disease as a collective experience that foregrounds how we experience our bodies in relation to one another. Contemporary medical research (understandably) focuses on tissues and organs or the medical profession’s relation to the patient, but the patient’s living body within a network of meaningful relationships with others is often confusingly absent. With ‘total pain’, Saunders attempted to remind doctors that the dying patient is a person too, with a present body, an existing social network and a complex past, all of which may contribute to their current pain. In attending to these complex relationships, both Saunders and Defoe acknowledged how the ‘strange times’ of terminal illness or contagious disease can be isolating and stressful, but how they also have the power to bring us together.

References

Butler, R. N. (1963) ‘The Life Review: An Interpretation of Reminiscence in the Aged’, Psychiatry. Routledge, 26(1), pp. 65–76. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339.

Defoe, D. (2010[1722]) A Journal of the Plague Year. Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics

Gunaratnam, Y. (2012) ‘Learning to be affected: Social suffering and total pain at life’s borders’, Sociological Review, 60(SUPPL. 1), pp. 108–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02119.x.

Saunders, C. (1984) ‘On dying well’, Cambridge Review, (27 Feb), pp. 49–52.

Segal, L. (2013) Out of Time: The Pleasures and Perils of Ageing. London: Verso.

Thanks Joseph, been 32 years since I read Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year but I well remember the amazing sense of it being a factual account. Much later I discovered what you will of course know better than me, that Defoe was very young, about 5 (?) when the Plague started. So, while early impressions can be powerful, presumably most of the text is a fictional reconstruction – and all the more stunning as a result. Was also interested in what you say about time and wondering if you’ve had any thoughts about the constructed nature of time – i.e. that the pandemic has disengaged a lot of people from the multiple signifiers of time (clocks, appointments, traffic noise, etc.)? An approaching death (for the dying person and anyone else closely involved) must do something similar as the externally constructed nature of one’s time loosens its apparent hold, as the very nature of one’s reality changes consciousness itself?

Thanks for your comment Ralph. I would have said the Journal was pretty much all made up from Defoe’s imagination and other first-hand reports and sources, but I really like your suggestion that he might have been communicating the sense of dread he experienced as a young child!

In terms of the pandemic disengaging us from time, I reckon it’s a double bind for some. The aural rhythm, particularly of the city, has abated but the importance of turning up at virtual meetings on the hour or fitting all your work around shared parenting or caring responsibilities might actually make people more aware of their position in clock-time. On the other hand, someone who is furloughed (and furloughed happily) could potentially be enjoying a sense of timelessness, or even synchronising themselves with the sun.

I agree that knowledge of an approaching death might specifically challenge a sense of constructed time. Saunders very much saw her hospice as a village in opposition with the noisy urban sprawl of a large tertiary hospital. Her routine of regular preemptive morphine and no set visiting hours can be seen as primarily giving patients and their families time to be together in a way that they would not have been able to according to the temporal strictures of their normal lives. Marion Coutts’ book The Iceberg is excellent for describing this kind of ‘hospice-time’.

More generally, Saunders and ‘total pain’ chime with more current ideas about interoception or the gut-brain axis in suggesting that bodily changes might affect cognition and consequently comprehension of time. For Saunders, though, such temporal changes would have been associated with the timelessness of the afterlife. She was very interested in the Swiss theologian Ladislaus Boros whose book The Moment of Truth suggests that when we die we experience a final moment of decision outside of all time in which we comprehend the whole of our life in the context of the ‘totality of reality’ and choose to turn to God.

Thank again for your comments.